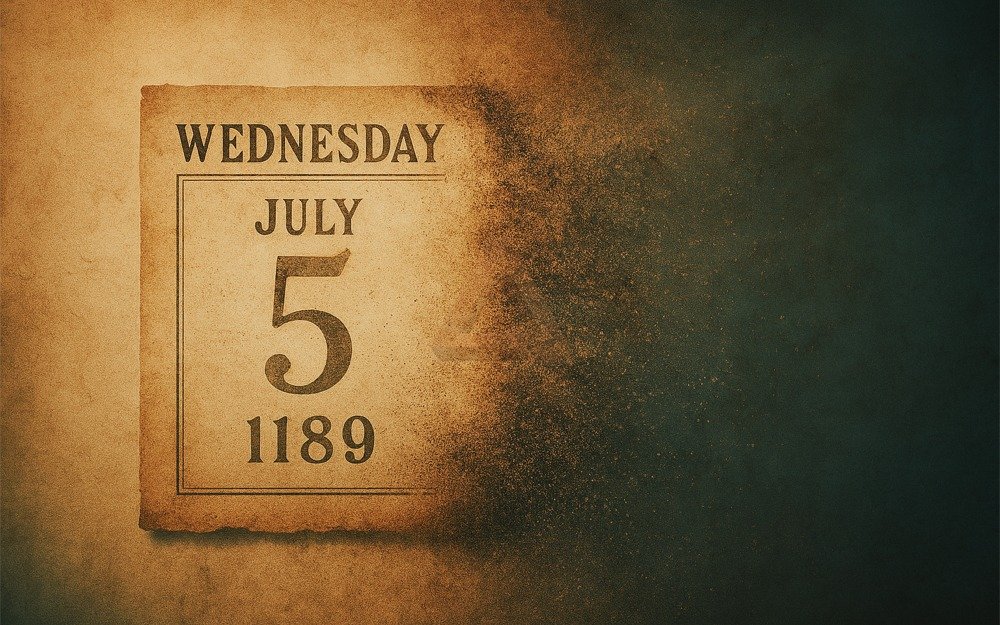

In English law, the term time immemorial isn’t just poetic — it’s procedural. It marks the point where evidence gives way to presumption, and history becomes legal fiction. While the term often evokes ancient custom or forgotten origins, its legal definition was fixed with surprising precision in the 13th century. This post explores how July 6th, 1189 — the day Richard I ascended the throne — became the official threshold of legal memory, and why the day before was lost in the eyes of the law.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines time immemorial as “a time in the past that was so long ago that people have no knowledge or memory of it”. In everyday use, it suggests something ancient, unrecorded, or culturally embedded. But in English legal history, the term was scoped with far more precision.

Before the 13th century, courts accepted claims to rights, privileges, and customs based on continuous use — regardless of whether written records existed. If a claimant could convince judicial authorities that their entitlement stretched beyond living memory, it could be recognised. This practice encouraged embellished recollections and, at times, forged documentation.

The Statute of Westminster (1275) and July 6th, 1189

Parliament fixed the boundary at July 6th, 1189 — the day Richard I took the crown. It was a Thursday. From that point forward, claims predating that date were no longer admissible. As a result, Wednesday, July 5th, 1189, and all days preceding it, were considered lost in the eyes of the law — erased from judicial memory.

This legal fiction gave courts a fixed point from which to measure prescriptive claims. It simplified disputes, but also erased centuries of unwritten tradition from formal recognition. The choice of Richard I’s accession was symbolic: a clean break from prior reigns, and a monarch associated with strength and clarity.

Prescriptive Rights and Property Claims

Under common law, prescriptive rights refer to entitlements acquired through long-term use — such as access to land, water, or easements. Before 1275, such claims could be based on oral tradition or local custom.

After the statute, they had to be traceable to the fixed date of 1189. The statute reduced ambiguity, but at a cost. It elevated documentation over memory, and formality over lived tradition. In doing so, it created a tension between civic memory and judicial recognition — a tension that still echoes in property law today.

Modern Echoes in Land Law and Civic Memory

Even in the 19th century, courts continued to reference time immemorial as a legal concept, though its application became more flexible. Today, many land titles in Britain still trace their legitimacy to claims recognised under the terms of the 1275 statute.

Beyond the courtroom, the phrase survives in folklore, civic storytelling, and cultural shorthand. It evokes a sense of permanence, even when the legal boundary is clearly drawn. And while Wednesday, July 5th, 1189, may be lost to judicial oblivion, the idea of time immemorial remains embedded in the architecture of law and memory.

Folklore, Custom, and the Limits of Legal Recognition

Beyond the courtroom communities pass down land use customs through stories, not statutes. A path worn through generations, a gate left open by agreement, a right to gather water from a shared stream — these things are remembered, not recorded.

But folklore doesn’t always survive judicial scrutiny. Courts ask for documentation. They want dates, deeds, and proof. What’s lived may be dismissed. What’s remembered may be ruled inadmissible.

Legal Fiction and the Architecture of Memory

The decision to fix time immemorial to July 6th, 1189 was not based on historical consensus — it was a legal fiction.

Parliament didn’t choose July 6th, 1189 because it marked a natural boundary. It needed a date — something clean, defensible, and symbolically distant. Richard I’s accession offered that. The choice wasn’t about history; it was about legal architecture. Draw a line. Fix a threshold. Let the rest fall into silence.

Other legal systems have drawn similar lines — each in their own way. Roman law used Usucapio, a possession-based claim that allowed ownership after uninterrupted use. But the rules weren’t fixed. Duration varied depending on the object, the claimant, and the social class involved. It was less about the calendar, more about continuity.

Napoleonic France took a different approach. The Code Civil introduced fixed prescription periods — codified thresholds that simplified disputes and reduced ambiguity. The goal was clarity, not consensus. Like England’s statute, it privileged legibility over tradition.

Modern systems continue the pattern. In the United States, Adverse Possession allows land claims after continuous, open use — often 10 to 20 years, depending on the state. No one invokes Richard I. No one needs to. The past is now measured in decades, not centuries.

England followed suit. The Prescription Act of 1832 replaced the old burden of proving time immemorial with statutory periods — 20 years for easements, 60 for profits à prendre. It was a practical move. Courts no longer had to entertain claims reaching back to Richard I. They could measure time in decades, not centuries.

But something slipped away. Oral tradition gave ground to statute. What had once been lived and remembered was now measured, filed, and timed. The perimeter narrowed — not by accident, but by design. Courts leaned on documentation. Memory became suspect, and ambiguity inconvenient.

Wednesday, July 5th, 1189, slipped through the cracks. Not forgotten — just rendered inadmissible. And yet, the architecture of human memory persists in the stories we reach for when the records run out.

Even if archaeology uncovers a parchment predating Richard I — a monarch’s grant of land in perpetuity — the statute holds firm. The past may be legible, even traceable, but the legal threshold remains fixed. The law wasn’t built to accommodate discovery; it was built to end dispute.

🔗 Think that was strange? There’s more. Explore our full Misconceptions Archive.

References

[1] Oxford English Dictionary | English. (2025). Time Immemorial. In Oxford English Dictionary Online. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 8 October 2025.

[2] legislation.gov.uk. (n.d.). Statute of Westminster, The First (1275). Retrieved 8 October 2025.

[3] Wikipedia. (2023). Time Immemorial. Includes discussion of the Prescription Act 1832 and its impact on legal memory. Retrieved 8 October 2025.