July 4th, 1826 — Fifty Years After Independence

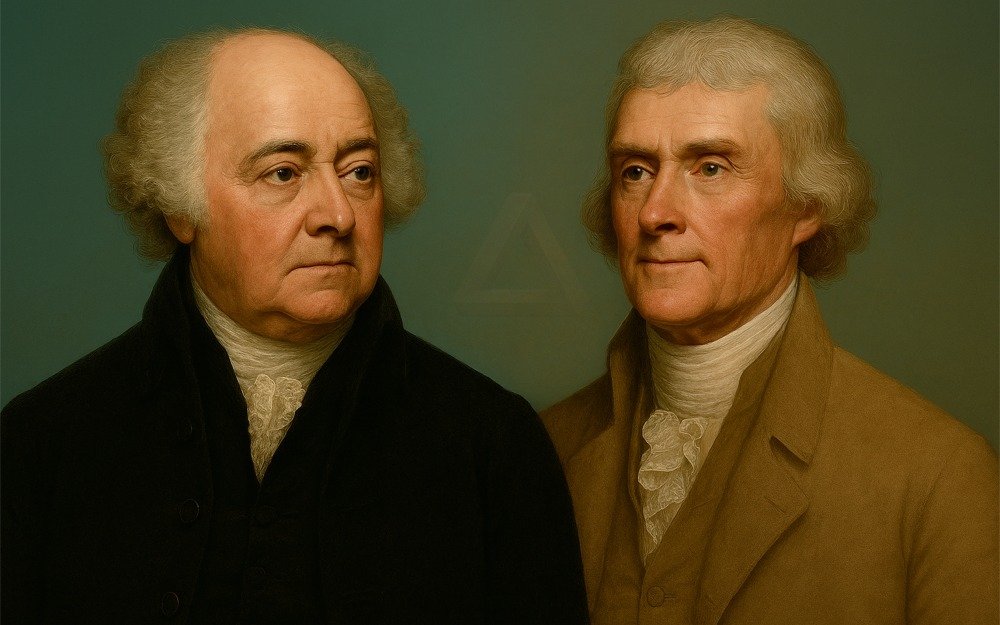

John Adams and Thomas Jefferson died within hours of each other on July 4th, 1826. Both men were of advanced age — Adams was 90, Jefferson 83 — and their deaths were not unexpected. But for the second and third presidents of the United States to pass on the fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, a document they had helped bring to life, was uncanny. It felt less like coincidence and more like divine providence.

The Writer and the Advocate

In June 1776, a five-man committee was tasked with drafting a Declaration of Independence. Jefferson was selected to write the first draft — not because Adams lacked the skill, but because Adams insisted the document should come from a Virginian, and Jefferson’s prose had a clarity Congress respected. Adams later recalled: “You can write ten times better than I can.”

Jefferson’s draft included a 168-word clause condemning slavery, blaming King George III for waging “cruel war against human nature itself” by perpetuating the transatlantic slave trade. It was a rhetorical maneuver — Jefferson, a slaveholder, was shifting moral blame onto the Crown. Adams admired the passage but predicted it would be struck. He was right. Southern delegates and Northern merchants with ties to the trade demanded its removal.

Adams, unlike Jefferson, never owned slaves. He employed free labour and voiced opposition to slavery throughout his life, though he resisted radical abolitionism. Jefferson, by contrast, kept hundreds in bondage — even as he wrote that “all men are created equal.” The contradiction remains one of the Declaration’s deepest fractures.

Their synergy in 1776 was real: Jefferson shaped the text; Adams secured its adoption. One gave it voice, the other gave it velocity and got it over the line in Congress.

Jefferson’s Deleted Clause

Note: This clause blamed King George III for perpetuating the slave trade. It was removed under pressure from Southern delegates and Northern merchants.

Note: The omission left the Declaration silent on slavery — a silence that echoed through American history.

From Patriots to Political Enemies

By the late 1790s, the friendship had soured. Adams, now president, faced opposition not just from Jefferson’s party — but from Jefferson himself, who as vice president quietly funded partisan attacks through newspapers like the Richmond Examiner and Aurora. His surrogate, James Callender, accused Adams of warmongering, monarchism, and moral depravity. The most infamous smear described Adams as having a “hideous hermaphroditical character”.

Adams refused to campaign. Jefferson stayed silent; Callender didn’t. The misinformation campaign worked. Voters believed Adams sought war with France. He didn’t. But the damage was done. Jefferson won the 1800 election, and Adams left office feeling bitter and betrayed.

The rivalry had become personal. They were no longer ideological opponents. They were enemies. And yet, twelve years later, they began writing to each other again

Reconciliation Through Letters

Time had helped quench their bitterness. In 1812, at the urging of mutual friend Dr. Benjamin Rush, Adams reached out. Jefferson replied. What followed was a remarkable correspondence — over 150 letters exchanged across fourteen years. They debated philosophy, governance, and mortality. Their letters were honest, thoughtful, and frequently warm.

Correspondence Reborn

Note: This letter marked the rekindling of their friendship after twelve years of silence. Jefferson’s tone is warm, reflective, and steeped in shared memory.

Note: The letters became a model of civil discourse between ideological opponents turned friends.

A Nation Under God

Their deaths on July 4th, 1826 — Jefferson in Virginia, Adams in Massachusetts — felt mythic. Tradition holds that Adams, unaware Jefferson had already died, whispered: “Thomas Jefferson still survives.” Americans saw divine symmetry in the timing. Two founders, reconciled in life, departing together on the nation’s golden jubilee. It fed the idea of manifest destiny — that America was not just a republic, but a providential experiment approved by the almighty.

Five years later, James Monroe died on July 4th, 1831. Three of the first five presidents gone on the same date. Coincidence? Perhaps. But in the American imagination, it became something more.

🔗 Think that was strange? There’s more. Explore our full Oval Office Oddities archive.

References

[1] Ferling, J. (1992). Adams vs. Jefferson: The Tumultuous Election of 1800. Oxford University Press.

[2] Jefferson, T. (1776). Draft of the Declaration of Independence. Library of Congress. Source of the deleted slavery clause: “He has waged cruel war against human nature itself…”

[3] Cappon, L.J. (Ed.). (1959). The Adams-Jefferson Letters: The Complete Correspondence Between Thomas Jefferson and John Adams. University of North Carolina Press.

[4] Ellis, J.J. (1993). Passionate Sage: The Character and Legacy of John Adams. W.W. Norton. Details Adams’ views on slavery and his lifelong use of free labour.

[5] Meacham, J. (2012). Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power. Random House. Explores Jefferson’s rhetorical strategies and the political compromises behind the Declaration’s edits.

[6] Smithsonian Magazine. (2006). Adams and Jefferson: A Revolutionary Friendship. Retrieved September 2025.

[7] National Archives. (n.d.). The Declaration of Independence: A Transcription. Retrieved September 2025. Official record of the final Declaration text, excluding Jefferson’s slavery clause.